I don't know who you are Creaturebuilder, but dude, I like your style - and taste in music!

Monday, 26 October 2009

Sunday, 25 October 2009

Hot Joe (sporadically 1987 - 94)

It's a curious and oddly satisfying thing to have a band take shape around you, and then to watch it take on a life of its own in your absence, both when you're out of the country and also back in again. Such was the case with Hot Joe, still one of Memphis' finest and weirdest groups, in my humble and probably irrelevant opinion.

As a natural extension of the friendship between Linda Heck and The Train Wreck and K9 Arts, I started hanging out with K9 guitarist Jim Duckworth and my band mate John McClure in 1987 and working up some songs, mostly old standards, with me as the vocalist. Jim had an amazing music collection and an encyclopedic knowledge of jazz from its earliest roots to the modern experimental scene, and he turned me on to a lot of wonderful music. These afternoons spent at Jim's house were usually accompanied by copious amounts of coffee, so naming the group was a very easy exercise indeed.

Our first gig was with Rich Trosper on drums, I believe at some sort of art opening or party in Downtown Memphis, though the venue and occasion totally evades me, probably because I was fairly terrified at the time by the prospect of fronting a band as vocalist for only the second time ever. I can't recall exactly what our set was, but it contained "Cheek to Cheek," "Moody's Mood for Love," "Strawberry Fields Forever" (yes, a straight jazz version), and God knows what else. At some point we debuted a version of "Ornithology" with original lyrics by me, which so exited an apparently well-known local "jazz dude" in the audience that said enthusiast mounted the stage and commandeered the microphone to "scat". I've always hated scat. I was very irritated by this man at the time, but ended up being mightily amused by the fact that, whenever the imperious scat-cat wannabe in question ordered (rather than requested) Rich to "lay out," Rich responded with a very loud rim-shot or flam of some sort to piss the interloper off. Eventually he gave up and left the stage.

From these humble beginnings arose Hot Joe, and the group, in various permutations, began to get real paying gigs, mostly weddings and cocktail receptions, which, in addition to a civilized audience and a guaranteed pay check, also typically included free food and drink - not a bad alternative to the thankless smoke-filled dives we were used to. The line-up of the group evolved over time, though the core was typically Jim and John, plus Jim Spake on saxes and either Ross Johnson or Doug Garrison on drums (sometimes both together). On a couple of occasions Jim Duckworth had other obligations, and I recall doing two nice gigs with John Gaskill (a wedding) and Ed Finney (some sort of corporate event in the garden at Brooks Museum) on guitar. I was intrigued by Ed, who wore a compass on his wrist as opposed to a watch - which he explained something along the lines of "I may not be on time, but at least I know which way I'm headed."

Sometime after I left for Japan in 1988, Robert Palmer turned up in Memphis and became part of the band - his skronky clarinet an interesting foil to Jim Spake's refined playing. This line-up, which often included both drummers, became very popular over the next two years, and while maintaining the civilized paying gigs, also played harder-edged material in the clubs. They worked up a rocking mash-up of two of the best Mingus tunes, "Better Get Hit in Your Soul" and "Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting," a very fast, Klezmeric version of "Over, Under, Sideways, Down," with Jim Spake and Bob Palmer trading solos, and expanded "Strawberry Fields" into a long medley improbably including "Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough," "Haitian Fight Song," "The Immigrant Song," and "When the Saints Go Marching In." There were also a few fine originals by Jim Duckworth, including "Mimi" (a K9 Arts song) and "Jonah," which was a beautiful song, and Linda Heck's "Look Out for Love."

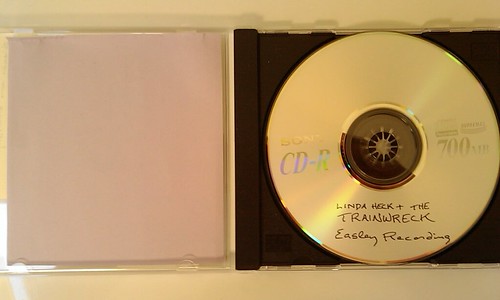

In the summer of 1989, I came back to Memphis during the summer break, and the guys very kindly arranged a recording session while I was in town, and we also played a gig at the P&H Cafe, which I think might have been a WEVL benefit. I don't remember that much about the gig, apart from the fact that we played versions of "My Favorite Things" and "'Round Midnight" with original lyrics I had written. The recording session, on the other hand, I remember very well, and still have tapes from it to remind me of what a pleasant experience it was. The full line-up (Jim D., Jim S., John, Ross, Doug, Bob, me and Linda Heck) went into Doug Easley's studio behind his house on Marion Street off South Highland on a Saturday night and recorded into the wee hours. We cut "Better Get Hit/Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting," "Over, Under, Sideways, Down," "Mimi," "Strawberry Fields Forever," "'Round Midnight" (with my lyrics), "Ornithology" (ditto), an old Linda Heck and The Train Wreck song "My Crying is Done," two versions of "Look Out for Love" (one with Linda on vocals, and an "answer version" with me substituting my own lyrics), and a very short "Cottontail." It was a blast, and the music still sounds wonderful today.

Jim Duckworth drove me back to my parents' house that night, and Bob Palmer, who was along for the ride, regaled us with some very funny stories of his adventures. My parents' house is not far from the home of the late Sam Phillips, whom I saw many times over the years mowing his own grass, and this triggered an anecdote from Bob, which he attributed to Sam Phillips himself. It seems that when Fidel Castro was in New York City in 1959, Sam Phillips managed to get the number of his hotel room, and possibly somewhat the worse for wear at the time, called it. Bob claimed that Fidel's brother Raul had answered the phone, and told Sam that Fidel was unavailable, to which Sam apparently said, "Well, I just want to wish him well with that revolution down in Cuba, but tell him that if it doesn't work out, he always has a home in Memphis, Tennessee, and that comes from Sam C. Phillips."

I have no idea whether this story was true at all, but I found Bob Palmer to be a delightful storyteller and a very funny man. And he was into Persian classical music, as was I, and I seem to recall we ended up talking about parallels between the Charles Mingus band in 1964 and Persian classical ensemble performances, which are punctuated by unaccompanied solo segments from each of the instruments. That was the sort of conversational side alley you could find yourself wandering down when talking to Bob Palmer. Wish I'd had a chance to get to know him better.

I would really like to see a comprehensive list of all the songs played during the life of Hot Joe, because it would almost certainly run to hundreds. The paying gigs, when they required a vocalist (which was by no means always the case) often came with an obligation to learn some new songs, and I recall that we worked up a really nice version of "I've Never Been in Love Before" for some newlyweds' first dance, and another couple wanted the Beach Boys' "Wouldn't it be Nice?" for their first song. We played it faithfully, and luckily I have a pretty wide vocal range, because it's a hell of a song to sing as the first of the night.

The paying gigs, particularly the corporate stuff, gave license for some fairly subversive material, because typically no one was really paying attention, so it was not uncommon to hear the likes of "See Emily Play" slipped in among the Chet Baker numbers. It was also an interesting opportunity to observe people, because the band members were typically ignored and I was singing maybe one in three songs, so I had ample opportunity to look around the room. At one wedding reception, I remember Jim Spake was featured on a particularly fine version of (I think) "In a Sentimental Mood" and a very old woman stood close by and cried her eyes out until someone took her back to her seat to comfort her.

My abiding memory of the remarkable experiences I had with this group, beyond the awesome recording session, was a Christmas show we did on Wally Hall's Memphis Beat program on WEVL, I believe in 1991. The full line-up was there, minus Bob Palmer, and Linda Heck and I traded vocal duties, teaming up on "Let it Snow, Let it Snow, Let it Snow" and "Christmas Time is Here." The evening ended with me behind Ross' drum kit beside Doug Garrison as we all accompanied Ross doing a predictably hilarious reading of "The Night Before Christmas" (including ad libs such as in the description of Santa Claus, "There were broken veins in his nose - he'd been drinkin'") which I have on tape somewhere and is still one of the funniest things I have ever heard.

I always enjoyed getting to see these guys play up close - being allowed to sing with them, and even getting paid, was purely a bonus.

Wednesday, 21 October 2009

Wednesday, 14 October 2009

Monday, 12 October 2009

The Great Memphis Earthquake of 2003

Back in the 1980s, Memphis was still struggling to come to terms with the disregard it had shown for its musical heritage. The Beale Street renovation wasn't complete until October 1983, and even with this positive step forward, it felt to me (and I'm sure I wasn't alone) that the comeback strategy was more about emulating Bourbon Street than about highlighting what was really special about the musical legacy. It's not as if there was any shortage of raw material to work with at that time, but opportunities were missed or deferred, and the city still has a lot to answer for in its treatment of both people and historical sites - I still find it unfathomable that both the Stax and American studios were demolished. It was a time when giants wandered forgotten and unrecognized. On the positive side, there was always a chance that you could run into a hero or two if you were in the right place at the right time.

Sometime in 1983, I remember dropping by Dan and Linda's "Green Acres" shack in Binghampton, and there sitting on the sofa, was an older man who was introduced to me as Paul Burlison. I mean, Paul Burlison, hanging out in the ghetto with some impoverished kids, goddamn! Someone told me later that he hadn't touched a guitar in years at that point, and might have even forgotten some of the old Rock-n-Roll Trio numbers.

Sometime in the winter of 1987/88, Hans Faulhaber, an architect and musician I knew, invited me to play rhythm guitar on a single he was going to record at Phillips Recording, around the corner from Sun Studios. Just the chance to set foot in such a hallowed studio again (I had done another session there in 1984) was enough for me, but to make it even better, I was going to get to play with Roy Brewer (drums), Doug Easley (bass), and Bruce Lester, the lead guitarist from The Beat Cowboys, a hot-ass Nashville-style guitar picker of the Telecaster-slinging variety. I think I was going to get paid too, which was a rare surprise in my musical career. But the real surprise was still in store, for when I arrived at the studio, I discovered that the session was going to be engineered by none other than Roland Janes. Roland Janes - the most influential and recognizable unknown guitarist of his age, creator of some of the wildest and most provocative guitar stylings of the rock-n-roll era.

He was a really nice man, very funny and curious about things. There didn't seem to be that much going on at Phillips Recording back then, and I don't know how connected to the wider music world he really was at that point. Like Paul Burlison, he was eventually given the attention and recognition he so richly deserved, but at that point in time I sense that he was still living through the nuclear winter which all but the most popular of his generation were enduring. As he and Doug were setting the levels on the drums, I was already in position with the acoustic guitar, absentmindedly playing and singing a few songs to amuse myself, one of which was an early Beatles' song, possibly "I Should Have Known Better." Roland hit the studio intercom button. "What's that song you're playing? I like that." He didn't seem overly familiar with the Beatles' catalogue. George Harrison would probably have given his favorite sitar for a chance to be there with that man just then, and he (Roland) may not really have had that much idea of his own influence on the world. Presumably he got some inkling once things picked up for him.

We recorded two songs that day, written and sung by Hans, and released as a 45. The songs were:

Evil - A song inspired by an altercation with some belligerent rednecks at (I believe) an Elvis Costello show. It was a fast country number with some unbelievable guitar playing, and an almost out-of-control vocal performance by Hans.

"There's evil in the home of rock-n-roll,

Of that I'm sure, how much I just don't know,

It comes out in the night,

It's dressed in red and it likes to fight,

I don't."

2003 - This was an odd sort of loping country-reggae song, which I would really like to hear again if I could only find my copy. It's the only song I can think of on the topic of earthquake preparedness, something which Hans, as an architect, was very concerned about - with just cause, of course, because the last major New Madrid Fault quake was so fierce that the Mississippi flowed backwards in some places and church bells rang on the East Coast. In the last line of the song, he sings, "I can't say when it will be, my choice would be 2003." Indeed 2003 seemed to be a long way off back in 1987, but it sure came and went fast, luckily with no earthquake. That's no excuse for complacency.

"Big quake's comin', now you better beware,

It's gonna get the best of me and you,

It's gonna tumble old Memphis down,

We're gonna really be the Home of the Blues.

That fault's gonna open so wide,

Ain't gonna be no place to hide.

It happened here once before,

When we weren't even around,

Next one's gonna be twice as bad,

It's gonna shake this city down.

That fault's gonna open so wide,

Ain't gonna be no place to hide.

So get your people settled down,

And talk to 'em logically,

Explain in no uncertain terms,

What is and what will be,

Prepare them for the time,

They gotta start a brand new life,

They gotta start out on their own,

They gotta build a brand new home."

I always really liked this song, both the music and the message, which still seems to go largely unheeded. Hans delivered my copy of the single in person, when he came to visit me in Tsuru City, Japan, shortly after I moved there on a two-year teaching gig in August, 1988. We hung out for a week, he played me some amazing recordings he had made with Tommy Hull, and I even arranged a few proper Japanese earthquakes for him.

Sometime in 1983, I remember dropping by Dan and Linda's "Green Acres" shack in Binghampton, and there sitting on the sofa, was an older man who was introduced to me as Paul Burlison. I mean, Paul Burlison, hanging out in the ghetto with some impoverished kids, goddamn! Someone told me later that he hadn't touched a guitar in years at that point, and might have even forgotten some of the old Rock-n-Roll Trio numbers.

Sometime in the winter of 1987/88, Hans Faulhaber, an architect and musician I knew, invited me to play rhythm guitar on a single he was going to record at Phillips Recording, around the corner from Sun Studios. Just the chance to set foot in such a hallowed studio again (I had done another session there in 1984) was enough for me, but to make it even better, I was going to get to play with Roy Brewer (drums), Doug Easley (bass), and Bruce Lester, the lead guitarist from The Beat Cowboys, a hot-ass Nashville-style guitar picker of the Telecaster-slinging variety. I think I was going to get paid too, which was a rare surprise in my musical career. But the real surprise was still in store, for when I arrived at the studio, I discovered that the session was going to be engineered by none other than Roland Janes. Roland Janes - the most influential and recognizable unknown guitarist of his age, creator of some of the wildest and most provocative guitar stylings of the rock-n-roll era.

He was a really nice man, very funny and curious about things. There didn't seem to be that much going on at Phillips Recording back then, and I don't know how connected to the wider music world he really was at that point. Like Paul Burlison, he was eventually given the attention and recognition he so richly deserved, but at that point in time I sense that he was still living through the nuclear winter which all but the most popular of his generation were enduring. As he and Doug were setting the levels on the drums, I was already in position with the acoustic guitar, absentmindedly playing and singing a few songs to amuse myself, one of which was an early Beatles' song, possibly "I Should Have Known Better." Roland hit the studio intercom button. "What's that song you're playing? I like that." He didn't seem overly familiar with the Beatles' catalogue. George Harrison would probably have given his favorite sitar for a chance to be there with that man just then, and he (Roland) may not really have had that much idea of his own influence on the world. Presumably he got some inkling once things picked up for him.

We recorded two songs that day, written and sung by Hans, and released as a 45. The songs were:

Evil - A song inspired by an altercation with some belligerent rednecks at (I believe) an Elvis Costello show. It was a fast country number with some unbelievable guitar playing, and an almost out-of-control vocal performance by Hans.

"There's evil in the home of rock-n-roll,

Of that I'm sure, how much I just don't know,

It comes out in the night,

It's dressed in red and it likes to fight,

I don't."

2003 - This was an odd sort of loping country-reggae song, which I would really like to hear again if I could only find my copy. It's the only song I can think of on the topic of earthquake preparedness, something which Hans, as an architect, was very concerned about - with just cause, of course, because the last major New Madrid Fault quake was so fierce that the Mississippi flowed backwards in some places and church bells rang on the East Coast. In the last line of the song, he sings, "I can't say when it will be, my choice would be 2003." Indeed 2003 seemed to be a long way off back in 1987, but it sure came and went fast, luckily with no earthquake. That's no excuse for complacency.

"Big quake's comin', now you better beware,

It's gonna get the best of me and you,

It's gonna tumble old Memphis down,

We're gonna really be the Home of the Blues.

That fault's gonna open so wide,

Ain't gonna be no place to hide.

It happened here once before,

When we weren't even around,

Next one's gonna be twice as bad,

It's gonna shake this city down.

That fault's gonna open so wide,

Ain't gonna be no place to hide.

So get your people settled down,

And talk to 'em logically,

Explain in no uncertain terms,

What is and what will be,

Prepare them for the time,

They gotta start a brand new life,

They gotta start out on their own,

They gotta build a brand new home."

I always really liked this song, both the music and the message, which still seems to go largely unheeded. Hans delivered my copy of the single in person, when he came to visit me in Tsuru City, Japan, shortly after I moved there on a two-year teaching gig in August, 1988. We hung out for a week, he played me some amazing recordings he had made with Tommy Hull, and I even arranged a few proper Japanese earthquakes for him.

Labels:

Doug Easley,

Hans Faulhaber,

James Enck,

Paul Burlison,

Roland Janes,

Roy Brewer

Sunday, 11 October 2009

Liner notes to "The Lost Album"

I had a long Skype chat with Linda Heck yesterday, ahead of her solo gig at Otherlands in Memphis. She said in passing that she had always had an awful lot of material beyond what the band played, which I guess I should have expected, but this revelation still took me by surprise. I have never heard this stuff, and maybe no one else has either. The mind boggles. During its various incarnations, my guess is that the total Train Wreck repertoire of Hecktunes ran to 60 songs, or thereabouts. The 21 songs on what I have taken to calling "The Lost Album" are a pretty representative cross-section of the material the band played during its life, with a bias towards material written in the later period, when Linda had really hit her stride.

Sometime during the final incarnation of the band in 1988, Linda had begun seeing Clayton Rogers, to whom she is now married. Clayton lived in the same building as our mutual friend Belinda Killough, and became part of the social circles in which we all shuffled. I have always been surprised that we hadn't met previously. He was raised in East Memphis, as was I, and we knew a lot of people in common (he went to MUS boys' school, the Midtown contingent of which I knew because some of them dated girls in my high school). Clayton is wicked smart, with a surreal sense of humor, and is a very generous person. A talented architect, he totally revamped the big house they ended up buying on Madison in Midtown after I returned from Japan in 1990, which had been a doctor's office for years and was in need of a lot of loving care. It was a fairly Herculean task, having seen it in its unadorned state, but he and Linda made it something truly impressive during the time they were there, as an expression of their shared love of design and all things cool.

Clayton's father had died unexpectedly some time before, at a tragically young age, and had left him some money, a part of which he decided should go to fund a proper recording session for Linda and the band. Sometime in the late spring/early summer of 1991, we went into the fantastic Easley-McCain studio (back then it was known simply as Easley Recording) to begin work. I had visited the studio when it was still in the process of refurbishment from the dilapidated state in which they acquired it, and had also seen photos of what it looked like before it had been touched. Doug Easley and Davis McCain had worked wonders with it. It was an amazing place to be, and I always looked forward to going there, as I would do for various sessions over the years, or just for a social visit. A rather unassuming building from the outside, it had a nice, homey feel to it inside, with a comfortably decorated reception/chill-out lounge just inside the door, leading to the control room and main room. There was an office upstairs, where presumably Chips Moman sat at a desk at some stage counting his gold records, and as I recall there were two reverb chambers running vertically through the building, which were actually used from time to time. The main room was colossal, maybe something like 1600 square feet, with three isolation booths, and what must have been a 40-foot ceiling. My estimates of dimensions may be off a little bit, but to put things in perspective, you could have comfortably fit a small symphony orchestra in the main room with no problem.

Working with Doug and Davis was a great experience. We had known them for years and all got on very well. I had first seen Doug playing in a band with his brother Ron and Bob Holmes, later of the Modifiers, at a fraternity party at MSU in 1980 - I was there because some of the older guys I worked with were members. Davis I met probably in 1981/2, when I unsuccessfully auditioned to be the second guitarist in his band Barking Dog. Davis was later the sound man at The Antenna Club for a number of years, and I think this experience of doing things under pressure and being pragmatic was one thing which made him so easy to work with in the studio. It always struck me that Doug and Davis were more concerned with capturing a vibe or performance when the timing was perfect than with over-engineering things. In contrast, I remember a session I once worked on at a different studio, wherein the miking of the drums alone took four hours, during which I lost the will to live, let alone record. Doug had a particular talent for surrendering to serendipity and accidents that occurred, and letting them guide the process, which suited me fine.

We initially recorded the basic tracks over three or four sessions, in three different configurations based on who was drumming. As had been the case through too much of the band's life, it was the ever-rotating drum stool which drove the process. Doug Garrison (whom we had played with in Hot Joe, but who will be better known for his work with Alex Chilton, Charlie Rich, and The Iguanas) graced us with some fine drumming on seven songs, Ross Johnson played on five songs, and I played on the other nine. We were joined on four songs by Jack Adcock (611, The Bum Notes, Professor Elixir's Southern Troubadors) on miscellaneous percussion. Jim Duckworth (Panther Burns, The Gun Club, Marilyn and The Monroes, K9 Arts, Hot Joe) played some characteristically beautiful guitar on four tracks, and the inimitable Jim Spake played sax on three tracks (should have been more!). Clayton contributed water-filled wine glasses and whirring plastic tubes to the eerie "Chalk Outline" track. Everything else was covered by Linda, John, and me.

Bafflingly, once we had recorded the basic tracks for 18 songs, the whole project seemed to go dormant for a year. Linda and Clayton had a lot of other stuff going on, as did we all, but in retrospect it strikes me as odd that, given how well those first sessions went, we weren't all impatient to finish things up. It was a more than a year later before we would return to the studio to do some refinements and mix. We realized we had more space left on one tape reel, so we quickly recorded three more songs, which are far less produced than most of the rest of the album, though I think they are all good performances: "When Water Burns," "If I'm So Smart," and "Sunday."

I am still very moved by this recording, a mixture of pride and nostalgia for what were very enjoyable sessions with wonderful people in the best studio in the world. I play it for my children from time to time, and they enjoy it as much for its musical merits as for their delight at the occasions where they can pick my voice out of the backing vocals. As with everything viewed retrospectively, I can hear things which I would want to do over if given a chance, and I would love to remix one or two songs completely. I am not sure if the master tapes even survived the fire at the studio in 2005, so the idea of remixing it one day may be a complete impossibility. Speaking strictly for myself, I think we could have spent more time differentiating some of the guitar parts and making them more forceful, but we had a fairly limited budget. It's always possible to over-analyze things across a temporal gulf such as that which separates me from these recordings, but as a package, I think they are wonderful just as they are. But don't take my word for it. Eight of the highlight tracks currently appear in the music player on Linda's MySpace page, so listen for yourself (these songs are marked with an asterisk below). Perhaps someday the entire album will see the light of day.

The Songs

1) Dig (also known as Dig My Own Hole)* [2:18]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - bass guitar

James Enck - electric guitar

Doug Garrison - drums

Jim Spake - baritone sax

Jim Duckworth - electric guitar

This song has been featured on a couple of compilations, and is something of a signature tune for Linda. An ode to defiance and self-reliance:

"Do my own thing in my own time,

I'll live my own life, speak my own lines,

My ears are closed, my shoulder is cold,

I'll make my own bed, dig my own hole"

Fantastic guitar work by Mr. Duckworth and a strong vocal performance by Linda.

2) Professor of Love [3:11]

Linda Heck - vocal, acoustic guitar

John McClure - upright bass, acoustic guitar, synthesizer (faux marimba sound)

James Enck - electric guitar, trumpet, backing vocal

Doug Garrison - drums

Jack Adcock - guiro

I never quite understood the derivation of this song, but I think it started from a character idea that Roy Barnes had come up with for a film - a mysterious expert in love for troubled hearts. Roy later shot a music video for this song, which did not, in fact feature a Professor of Love character. Would love to re-do the end of the guitar solo, but that's life. The rest of it is spectacular.

3) Failing Sky* [2:49]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - drums

Jim Duckworth - electric guitar

Jim Spake - tenor sax

One of my very favorites, with some really special guitar work from Jim Duckworth, and a splendid solo by Mr. Spake.

4) Laff* [2:06]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, electric guitar

James Enck - electric guitar, drums

Jim Duckworth - electric guitar

This song was written about Jim Duckworth as part of the K9 Arts trilogy, as I recall in recognition of his undying appreciation of all things Linda Heck and The Train Wreck. Jim laid down an intro part which was amazing but very heavy and a bit sinister, which we felt was out of character with the sentiment of the tune, so we stuck to his straightforward chordal accompaniment until the end of the song, when we faded in two lead parts. I was never sure that he was happy with this arrangement, but I think it works beautifully.

5) Sunday [2:21]

Linda Heck - vocal, acoustic guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - electric guitar, drums

A great song about self-realization, inspired by a long night out. This was probably the most basic arrangement on the entire album, and I like its understated quality. We recorded it pretty much on the fly at the end of the process, and it felt really nice at the time. Great vocal performance, and I still find it hard to believe that's me on the drums (ditto for the preceding track).

6) When Water Burns [2:53]

Linda Heck - vocal, acoustic guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - electric guitar, drums, backing vocal

This was a barn-burner from the Roy Brewer era of the band, which we decided to record at the end of the sessions when we realized we had tape left over. The bass isn't high enough in the mix for my liking, but it's a spirited performance.

7) If I'm So Smart [2:30]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - electric guitar, drums, backing vocal

A country rocker, also recorded at the end almost as an afterthought, but it's an honest and strong performance.

8) Every Mother's Son [2:55]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - upright bass

James Enck - drums, flute, recorder, bass recorder

A beautiful song, apparently about the uncritical love of a parent for a child, as observed by a third party. I had made a four-track demo of this with Linda (where is that, I wonder?), but we struggled a bit with this one. I suggested to John that he think about "Pet Sounds" for the bass part, and his playing really makes it what it is, and we later added a droning bowed bass part. Doug thought my flute/recorder bit sounded like a calliope, which I suppose it does. The reverb on Linda's voice is a tad overwrought. This is one I would remix given the chance, but it is still beautiful.

9) Chalk Outline [2:31]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - drums, electric guitar

Clayton Rogers - whirling plastic tubes, musical wine glasses, bathroom sink

Jack Adcock - nut shells, flexitone

The serenity of a picnic is rudely disturbed by the discovery of a chalk outline of a body.

10) It Is Alright* [2:35]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, piano, crash cymbal

James Enck - drums, electric guitar

Jack Adcock - vibraslap

This one still gives me goose pimples. Written for Linda's roommate of the time, Melissa Thornton. It's mostly Linda and John for two-thirds of the way, very subtle and beautiful, with a just a bit of cymbal work from me and Jack's vibraslap, but the ending I find uplifting, to match the message of the song. I had to overdub the crash cymbal with mallets to build up the suspense for the break to the finale, and then John (standing next to me) came in and knocked it home.

11) At A Party* [2:49]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - drums, electric guitar

This track, like the preceding one, is recorded with Linda playing a guitar strung with the high strings tuning (which Jones Rutledge describes as "Angel Hair") I alluded to in a previous post. This, coupled with my electric, occasionally sounds like a 12-string - very full. The arrangement is very simple, but it sounds complete, and I like my drumming here. The ending is a bit odd, and I'm not sure how that happened, or why we didn't fix it.

12) Magic Wand* [1:52]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, electric 12-string guitar, backing vocal

James Enck - electric guitar, backing vocal

Ross Johnson - drums

I think this may be one of the earliest Linda Heck songs I can recall hearing. I'm pretty sure it was on that original home demo cassette she returned to Memphis with in 1986. It's a great song about the desire for escape. One of the few occasions in which we attempted multi-part harmony, with good results. We should have done so more often.

13) House is Burning* [2:11]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - backing vocal

Doug Garrison - drums

Jim Spake - baritone sax

Jack Adcock - bongos

I think I was still stuck at work when this was recorded in a session starting at midday, but when I heard it I thought there was no need for another guitar because it sounded perfect as it was. And so it remained. As I wrote earlier, Cordell Jackson thought this song was about cocaine addiction, but anyone actually listening to the lyrics will realize it is about gossip and schadenfreude, recurring features of life in Memphis, and indeed anywhere where humans are present.

14) Split the Earth [2:34]

Linda Heck - vocals, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass

James Enck - electric guitar, backing vocal

Doug Garrison - drums

Another rocking song from the reinvigorated, newly empowered Linda Heck songbook of the 1987/88 vintage. I used to really enjoy playing this one live. I recall that Doug Garrison wasn't particularly satisfied with his playing on this track, but we assured him it was awesome, which it is.

15) Slipping Away [2:02]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - fretless electric bass, electric guitar

James Enck - electric guitar

Doug Garrison - drums

Some very dreamy guitar textures here, a nice melody line, and great lyrics about procrastination. John lays down a great lead guitar part, demonstrating why he was always more than just a pretty bass.

16) He Rode By [2:34]

Linda Heck - vocal, acoustic guitar

John McClure - upright bass, electric guitar

Doug Garrison - drums

The other song I missed due to the time slot, but there was nothing I could add. It is simple and elegant.

17) Today* [3:12]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, backing vocal

James Enck - electric guitar, backing vocal

Doug Garrison - drums

One of the very best Linda Heck songs, and one of the most exciting to play live in my opinion. Written for the late Craig Shindler to wish him well at a low point in life, it has a positive message characteristic of its vintage:

"Pain will go, before you know,

Let it fall away,

Happiness is within you,

And it can be today"

It's an unusual and intriguing structure, which is probably why I have always liked it, because it feels like it's always moving to a new level. Starting in C and reverting there for the bridge, switching to B for the verses, with the odd A to F-sharp interlude. Outstanding performance from Doug here, and I like the rising harmony vocals in the instrumental section. Linda is sublime throughout.

18) B-Movie [2:13]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, acoustic guitar

James Enck - electric guitar, backing vocal

Ross Johnson - drums

"'She's in the arms of another man,' he said,

'What should I do, shoot myself dead?'

Now wait a minute, that's quite extreme,

How dramatic, how B-Movie,

Is it worth it?

After all, just think how it would really be,

Just think how it would really be."

Great Nashville-style acoustic picking from John here, and I like the way my harmony voice only comes in as the voice of the lovesick loser.

19) Nightmare [2:18]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, acoustic guitar

James Enck - electric guitar

Ross Johnson - drums

A song, unsurprisingly, about a nightmare, apparently about being chased by dogs, but with a happy ending. Trippy, echo-laden vibrato guitar which I like.

20) Beer and Guitars [2:24]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, electric guitar, backing vocal

James Enck - electric guitar, backing vocal

Ross Johnson - drums

I can remember thinking at the time this song was written that it was a gentle joke, and perhaps it was, but as I grow older, I find it to be increasingly poignant. The title evokes the sign of Fred's Hideout (which featured a cartoon mug of draft beer and a guitar), our beloved dive of old where so many great shows took place, but which was also the home to many hopeless, broken alcoholics, whom this song seems to portray.

"Well there's nothing like whiskey and drums,

To ease the pain when it comes,

We see hope in each glass,

As we twiddle our thumbs,

There is nothing like whiskey and drums,

'Cept bourbon and rain,

And beer and guitars"

Beautiful volume-pedal guitar from John, approximating the sound of the honky-tonk pedal steel as it might have appeared on Sister Lovers.

21) 'Tis the Season [7:22]

Linda Heck - vocal, electric guitar

John McClure - electric bass, Hammond organ

James Enck - electric guitar, tenor sax

Ross Johnson - drums

Jim Duckworth - electric guitar

This was a song Linda wrote in 1987 for the 20th anniversary of the Summer of Love, which we used to do towards the end of shows at the time. The night that Ross sat in with us on short notice at Fred's Hideout in July 1987 to fill in for Roy Brewer after the birth of his first daughter Eva, we played a fairly raucous version of it, so it seemed natural to have Ross back for this recording. No one was disappointed. As I recall the song was vaguely inspired by a particularly demented contemporary Sky Saxon EP I had bought, and we pretty much cover all the psychedelic cliches here with feeling, including the "Helter Skelter" false fadeout and return (without which the track would be closer to ten minutes). Ross has the last words, which are "Ice cold Molson!" Amen.

*Available for streaming at www.myspace.com/thereallindaheck

All songs by Linda Heck.

Recorded at Easley-McCain Studios, Memphis, TN, summers 1991 and 1992.

Engineered by Doug Easley and Davis McCain.

Produced by Linda Heck, John McClure, James Enck, Clayton Rogers, Doug Easley and Davis McCain.

James Enck would like to thank all involved for a wonderful time, and the late Rich Trosper - whether you knew it or not, I was watching and learning. Thank you.

Saturday, 10 October 2009

Friday, 9 October 2009

A semi-random memory

My dad sent me an email this evening which triggered a memory I hadn't thought about for a while. In the summer of 1992, I was coming to the end of an unhappy year as a student in the urban planning graduate program at MSU. I had always been interested in urban planning, and still am (living in London, I am highly sensitive to the lasting effects of bad planning), and had entered the program with noble ideas of "making a difference." These were cured over the course of a year by interacting with people who actually were planners in Memphis, and seemed to be resigned to a life of despair, as well as one guy who had left a job as a telecom engineer with BellSouth, was about to get his Masters in planning, and faced the prospect of getting a job at half the level of his salary at BellSouth, if he could get a job at all. Clearly I was initially naive about the scope for planning to make any progress in America, and in Memphis in particular.

Anyway, this rather discouraging experience did give me one great anecdote. The professor I was assigned to as a research assistant was returning from an out of town trip, and had emailed me (my first use of email) to ask if I could collect her from the airport. One could say that this was an abuse of power, but I nevertheless agreed. She gave me her arrival time and said there was no need to park and come into the terminal. I should just wait in the car outside the arrivals hall. The problem being, of course, that you're not allowed (or at least you weren't back then) to just sit and wait, and as her flight seemed to be a little bit late, I could only keep circling around and back up the ramp to the arrivals exit. On my second lap, I slowed down to look inside the exit doors for any sign of her, but there was none. Just as I was about to drive off, I noticed a man standing by the exit with an unusual amount of luggage. No, I thought to myself, it couldn't be.

I drove around again, and returned to arrivals to still find no professor, but the man, a rather large black man in an avocado quasi-Elvis jumpsuit with cape, was still there, and I seemed to have caught his eye this time. I must have looked really stunned, and I remember smiling broadly at him. He smiled back, gave me the thumbs-up, and waved as I drove on. It was Barry White, waiting for his driver. I guess his career must have been at a very low ebb at that point. I hadn't thought about him in years, and it was long before the resurgence he would later properly enjoy. God knows what sort of ghastly gig he was in town for (and Barry had a lot of tough gigs), but it felt to me like he was really happy to see that someone recognized and remembered him. When I made my fourth and final lap, my professor was there, but Barry was gone.

Anyway, this rather discouraging experience did give me one great anecdote. The professor I was assigned to as a research assistant was returning from an out of town trip, and had emailed me (my first use of email) to ask if I could collect her from the airport. One could say that this was an abuse of power, but I nevertheless agreed. She gave me her arrival time and said there was no need to park and come into the terminal. I should just wait in the car outside the arrivals hall. The problem being, of course, that you're not allowed (or at least you weren't back then) to just sit and wait, and as her flight seemed to be a little bit late, I could only keep circling around and back up the ramp to the arrivals exit. On my second lap, I slowed down to look inside the exit doors for any sign of her, but there was none. Just as I was about to drive off, I noticed a man standing by the exit with an unusual amount of luggage. No, I thought to myself, it couldn't be.

I drove around again, and returned to arrivals to still find no professor, but the man, a rather large black man in an avocado quasi-Elvis jumpsuit with cape, was still there, and I seemed to have caught his eye this time. I must have looked really stunned, and I remember smiling broadly at him. He smiled back, gave me the thumbs-up, and waved as I drove on. It was Barry White, waiting for his driver. I guess his career must have been at a very low ebb at that point. I hadn't thought about him in years, and it was long before the resurgence he would later properly enjoy. God knows what sort of ghastly gig he was in town for (and Barry had a lot of tough gigs), but it felt to me like he was really happy to see that someone recognized and remembered him. When I made my fourth and final lap, my professor was there, but Barry was gone.

Thursday, 8 October 2009

Tuesday, 6 October 2009

Linda Heck and The Train Wreck (1986 - 88, 1990 - 93)

On January 29, 1986, I awoke for the first time in the foreign students' dormitory at the Kansai University of Foreign Languages, otherwise known as Kansai Gaidai, where I had enrolled for post-graduate Japanese language study, including the opportunity to live with a host family. Wandering into the day room, I found a large number of new arrivals and veteran students watching TV and trying to absorb the news of the Challenger Disaster. My first experience of Japan would both begin and end with incomprehensible, senseless loss.

A few days later, I met my host family, the Okutani's, who lived in Uji City, South Kyoto, roughly one hour's commute from campus. Hideo and Ryoko, the parents, were in their mid-40s, and their only child, Eiji, was 15. Hideo came from a large extended family in Kyoto and drove a cab at night, in his brother-in-law's taxi firm. Ryoko was a housewife descended from the landed gentry near Hiroshima, and in the eyes of the world (to the extent that it was interested), had almost certainly traded down the class ladder a couple of rungs, but clearly true love lay behind this choice. Shortly after I arrived, she had applied and been accepted to an evening degree program at a local university - a fairly unconventional thing for a middle-aged Japanese housewife to do in 1986. Eiji was pretty much a typical Japanese teenage boy - not particularly communicative, prone to oversleeping, very concerned with his appearance - but a sweet kid. They were a lovely family, and looked after me very well, taking me various places at the weekend and making an effort to speak to me in standard Japanese, as opposed to the mix of Kyoto and Hiroshima dialect they spoke to one another, which was pretty much incomprehensible to me when I first arrived.

In the spring, Ryoko started her evening classes, and as Hideo was driving his cab at night, Eiji and I were left to our own devices in the evenings. The first couple of nights we sat together and ate the dinner kindly prepared and left for us, and I understood that this was an opportunity to bond with him in a way which the dynamic of the home hadn't necessarily required or allowed before. I was pleased about this, because I felt that in the three or so months I had been there, I had so far been remiss. After a couple of nights as a duo, I was invited across the street to a neighbor's house for dinner, and to watch videos of their recent trip to Europe. Eiji was going out for a while to meet up with a friend. Unfortunately, this was a slightly older kid who had dropped out of school, gotten a job, and bought a powerful motorbike. A few hours later Eiji was dead, having broken his neck after losing control of his friend's bike and hitting a parked car.

In the interval between hearing this news of his injury (as it was first relayed) and his parents' arrival back at the home, I went out for a walk around the neighborhood to try to process this. Given that it was late at night, there was no one from the university whom I could call for advice. As I walked, I stumbled upon what I knew to be the site of the crash - broken glass, blood, a motorbike rider's glove. I knew he was dead. They returned later, thoroughly distraught, and the extended family began to arrive. To my surprise and distress, Eiji's body was brought back from the hospital and placed in the living room, where we all sat and cried into the morning. I went to school the next day to see what advice they had for me, but apparently this had never happened to a student before, and the Japanese staff in the office seemed to have no advice on funeral etiquette, which I found surprising and deeply disappointing. I returned home to find that a wooden altar had been assembled over Eiji's body, and this became the focus of attention in the days leading up to the funeral.

The school staff did at least manage to visit and to communicate to the family (who seemed unduly worried about how I was feeling) that I didn't wish to be a burden or source of stress during this terrible time, and I moved out for a few days during the preparations for the funeral. On the day, I, along with Sarah, the previous student lodger in the home, attended the funeral, which was open-casket at the front of the family home. Eiji's school friends filed past, in floods of bitter tears. Sarah and I were asked to accompany the family to the crematorium for the Buddhist cremation ritual, though, heart-breakingly Hideo and Ryoko could not attend, because, as it was explained to me later, the sect they belonged to had a prohibition against parents attending the cremation of an only child. We, and the family members in attendance, were ushered into a room where we were confronted with his bones and ashes, which we then took in turns to transfer to an urn. Obviously Sarah and I were totally unprepared for all of what we experienced, and found it very traumatic, but also felt deeply touched that the family had seen fit to include us in such a personal and intimate experience. I shall certainly never forget it, nor would I want to, painful as it still is.

Anyway, I moved back in, upon Hideo and Ryoko's clarification that they were genuinely happy to have me, and for a few months I carried on with the motions of going to classes, returning home in the evening to spend time with Ryoko, whom I had from the start been encouraged to call "Okaasan" (mother), though this seemed inappropriate now. I was running out of money and felt pretty beaten by the whole experience. I decided that I wouldn't look to get into part-time English tutoring, as did so many of my classmates, and would not renew for another semester. In retrospect, I think this was probably a mistake, but there was some subtle pressure coming from the extended family to stay on, find a nice Japanese girl to marry, settle down and become part of the family, which I viewed as natural in the circumstances, but not in anyone's best interest longer term. And I also felt like I needed to be back around my own family, and to try to make some sense of all this. So, back to Memphis I went, in the summer of 1986.

I arrived home to find the girlfriend I had left behind had moved on, and felt pretty much adrift and in need of something positive to pour my energies into. As it happens, around the same time, Linda Scheid had returned to Memphis with Dan Hopper after his Naval experience in Virginia. We got back in touch, and she revealed that she had written a lot of songs, and had produced a demo cassette of her playing guitar and singing her material, which I think was called "Comin' At Ya" and featured on the cover a cartoon self-portrait, though the "self" had a new name - Linda Heck. As I recall her explanation, the new surname was a sort of Southern trash tongue-in-cheek play on Richard Hell, which still makes me giggle to this day. We called in John McClure, with whom I had played in Four Neat Guys, and we were away. Precisely when we came up with the Train Wreck name for the band, or who thought of it, I don't recall, but it seemed to make sense as we were the result of several collisions of fate, and also because we individually had so many different influences.

We ended up recording three early demos with our first drummer, Harris Scheuner (also from Four Neat Guys), in his bedroom at his aunt's house in Midtown. We had a fairly poor borrowed 4-track cassette machine, which we only had for one day, so we worked quickly, cutting three pretty basic tracks: "So Long" (a fast country song which featured in early Linda Heck and The Train Wreck shows), "Doo Doot Doo" (an upbeat, poppy song which had a longer shelf-life), and "Too Bad" (a vaguely bluesy/rockabilly song with vocal harmonies). These are fairly noisy recordings (in the signal-to-noise ratio sense of the word), but listening to them now, I'm frankly pretty surprised that we had done three passable songs in a few hours with a poor set of tools and minimal preparation. "Doo Doot Doo" was entered into some sort of local demo contest, but generated no interest that we could detect.

Our first show was at the first-ever Hell On Earth at the old Bluff City Body Shop on Marshall near downtown Memphis (around the corner from both Sun Studios and Phillips Recording), an event which, I am told, continues every Halloween to this day in one guise or another, still curated by its founder Misty White. At that point in time, The Bluff City Body Shop was actually a working body shop, which Misty had managed to hire for the event. I clearly remember an almost overwhelming fug of auto paint and industrial solvent fumes, which seemed to drive many of the revelers outside during much of the event. There was also apparently some dispute between the owner of the P.A. system, John Paul Reiger, and Tav Falco, who was headlining, and this resulted in no P.A. or sound engineer materializing. We had to scramble quickly to find some solution, and ended up piecing together a few mics from the Four Neat Guys' rehearsal set-up, and used a bass amp for the vocals, which was terrible.

All in all, it was truly hell on earth - the room was hot, toxic fumes abounded, and the sound was diabolical. Things would improve in future iterations, as was also the case with the first Linda Heck and The Train Wreck set. I think Harris may have been a bit over-exuberant, because our set was played at break-neck tempos throughout. Linda seemed very annoyed with the whole situation, but we got through it and people seemed to enjoy it. I don't remember how or when we subsequently came to the conclusion that we needed a different drummer, but that was the view, which was hard to deliver because Harris was such a good guy. Obviously this decision triggered some sort of long-term karmic retribution, because throughout its life LHTW struggled more with drummer continuity than any other band, perhaps apart from Spinal Tap.

By the winter of 1986, I had bought my own 4-track cassette machine, and John, Linda and I spent some time working on new demos, with the vocals, rhythm guitar and bass recorded mostly in Linda and Dan's freezing apartment in the Cooper-Young neighborhood, where their feeble and senile downstairs neighbor would hallucinate wild parties happening upstairs, and was known on more than one occasion to appear at her cracked-open door with a small pistol in her trembling, bony hand. Having had a 22 pistol pointed at me in Overton Park a few years earlier, I was unenthusiastic about repeating the experience, particularly with a hallucinating old woman on the other end of the barrel, and I always felt decidedly nervous about coming and going in that old building. Anyway, with the basic stuff recorded, I would head back to my parents' house in East Memphis, where I would add drums, using my brother's drum kit, electric guitar, backing vocals, and whatever else seemed right. There were four songs which made it through this process to something like finished material: "Coming Up Roses" (which I always liked for its suspenseful stops and empty spaces), "No More Tears," "Carnival of Souls" and "Tired of All This Crying," all of which were features of early LHTW shows.

We played with a number of drummers during this period, including Jones Rutledge, Brenda Brewer, Ross Johnson, Jim Duckworth, and a few others we auditioned but never performed with. On one occasion, with no other alternative, I drummed at a show at The Antenna, leaving Linda strumming away on her electrified acoustic Silvertone, which sounded very strange on its own. A power trio we were probably not destined to be.

Linda and Dan moved to a house next to the Exxon on Madison at Belvedere, a property owned by Prince Mongo, whom I had first seen on TV shortly after moving to Memphis in 1974, in a news report about his eccentricities, during which he was lowered in a casket into a grave in his front yard. Many years later, he would attempt to return to Zambodia in a hot air balloon, but ended up having to make an emergency landing at Southwestern University, so I recall. Anyway, I saw him a number of times coming by to collect the rent during that period, and he was much more subdued than his public persona, though he did, in fact, address everyone as "spirit." John McClure ended up moving into the apartment across the hall, and we had ourselves a rehearsal space and recording studio.

We recorded two batches of songs during this period, in this house. The first eight were done in Linda and Dan's living room, and mostly used the same approach as previously - vocals, rhythm guitar and bass first, with me adding drums and other stuff back at home. However, on a couple of songs we were joined by Jones Rutledge, who stood on the long wooden staircase outside and played a piece of ceiling tile with a coat hanger, stamping his feet along, in place of drums. The first of these, "Can't Change Me," was always one of my favorites, and remained a fixture of shows later on, albeit with a "Paranoid" intro cheekily inserted by John and me. The demo version has me singing harmony below Linda throughout, which I like and should have tried more of through the years. Another song featuring Jones on lead staircase stamping, was "Look Away," one of Linda's early songs which we sometimes opened with. There was another song called "PTL (Pass the Loot)," a rare topical song by Linda and a swipe at Jim and Tammy Bakker. It's a song that got ditched later in live shows, but the recorded version has an "old time" gospel two-step break in the middle with hand claps, which may explain why we couldn't really do it justice in a live setting. "Ooh, That Girl" was written about someone who was annoying Linda at the time, and features John on some really over-the-top fuzz bass, some "La Grange"-style "haw, haw, haw" from Linda and some backwards guitar from me. "Skinny Little Thread" is one I always was proud of as a recording, because it seems perfect in spite of the primitive circumstances under which it was created. The vocal is recorded close and dry, and Linda really sings this one with understated conviction. It is a fine song. "Not Saved" was another early song which we never really got to grips with, as far as I can recall, though it is also a fine song. "It's True" is another beautiful country-tinged song with an undercurrent of unhappiness, on which I play a wooden box with some mallets constructed from segments of coat hangers wrapped in masking tape, in an attempt at an effect I think I heard on an NRBQ record around that time. Sadly, the vocals were recorded with too much reverb, which cast Linda down a deep aural well, never to return. The same is true of the country song "That Same Instant," featuring the same wooden box played with sticks, but redeemed by some fine guitar playing by John.

Around this time, uber-multi-instrumentalist Roy Brewer, who was living with his wife Brenda in Binghampton, had discovered a neighborhood bar which was open to having bands. I had passed it many times driving down Broad Street, but it was not the kind of place I would have ever considered going into, because it had all the outward signs of being a place where you could get open heart surgery at no charge. It had a sign featuring a guitar and a frothing mug of draft beer (which inspired Linda's later song, "Beer and Guitars") and was called Fred's Hideout, but it is better known to local hipsters today as The Cove. In 1987, it was not the kind of place I would have ever considered eating an oyster, if any had been on hand.

Alas, no oysters in 1987, only a small group of neighborhood folk who came in to drink too much at inappropriate times of day, and who were so starved of entertainment that they were willing to let a bunch of youngsters invade their home patch on Friday and Saturday nights in the hope of some break from drunken monotony. The proprietor was a likable chap named Bob Lightsey, who during the all-too-short reign of Fred's Hideout in the musical firmament, used to hold Sunday fish fries, and the like, for his new friends and the old regulars, who all mixed peacefully despite my early trepidations. He would also have the occasional after-hours lock-in, and on one occasion encouraged me to "Stay and git drunk if ya ain't got too far to drive." I passed, but this phrase persisted in the band for years. Fred's Hideout hosted shows by LHTW, The Odd Jobs, Marilyn and the Monroes, Harris and the Hepsters, The Brewers, and a lot of other bands (please help me remember them), and was a genuinely welcoming, friendly room to play in, with a tiny stage lined with mirrors behind, which always led me to suspect that some exotic dancing had taken place there at some point in the distant past. Again, as with many of the key turning points in the history of these bands, I can't recall how Roy Brewer came to be our drummer, but he did, and for once we had some continuity and sounded pretty good.

This lineup appeared on Andy Hyrka's local access cable TV show, and I think my parents still have a VHS copy of this at their house. It was a good performance, wherein we played "Look Out For Love" and "My Crying is Done," a stalwart of LHTW shows which we never recorded, apart from years later in the context of Hot Joe. This group also made a handful of recordings, in John's apartment, which by this time was set up as a primitive recording studio. "Desperate Man" was a straightahead rock song about a nine-fingered man Linda had known, and features John on some very wild distorted psychedelic guitar. "Eggziztence" was another favorite of the time, which live could turn into quite an angry workout, but recorded is a bit more tame. Fantastic lyrics, and a decent recording considering I was recording everything live in one room with no sissy baffling or other such trickery. "Off My Mind" always reminded me of a Jerry Lee Lewis song, so I put some minimal piano on it, and though it suffers from some guitar tuning issues, it has some nice three part vocal harmonies. "Lonely As Me" was another one of those rare recordings which just seemed to be perfect, and there's one moment in it that makes my hair stand on end to this day, when we all resolve together at the end of Roy's superb violin solo. "When Water Burns" became one of our barn-burners in live shows, and we later recorded it on "The Lost Album," but the Madison Avenue version features some nice harmonica by Roy, and some solid playing from everyone, slightly diminished by my stupid decision to put some chorus on Linda's voice, which is always best taken pure. There are a few other recordings sans Roy which were made around this time: "So Sorry" (a solo song inspired by a teen suicide pact in the news at the time), "Look Out For Love" (written for Amy Gassner and later a fixture of Hot Joe performances), "'Tis the Season" (a psychedelic blow-out written to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Summer of Love, a newer version of which closes "The Lost Album"), "Cool Breeze" (a nice bossa nova with John on guitar), and "Dear Diary" (a melancholy torch song which probably deserves to be revisited). All of the recordings I have discussed here lie dormant in my iTunes library, under the collective title "Lonesome Train on a Lonesome 4-Track." Perhaps some day they will be heard.

The group with Roy was as good as it had ever been, both musically and in terms of confidence. Roy had some definite opinions on presentation and the need to "sell" a performance (my words, not his), and I think we all took it on board. We were set to play a Saturday night gig at Fred's in July 1987, but Roy had become a dad, with the birth of his first daughter Eva. Ross Johnson filled in at short notice, and it was a very fun evening. I remember we did some unusual covers like "Hurdy-Gurdy Man" and also had a particularly good time with our show-closer of that era, "Serious About Rock-n-Roll." Being a dad, and having multiple other bands to play with and proper paying gigs to do, Roy stopped playing with us shortly thereafter.

Somewhere along in all this, Linda and Dan split up, and Linda moved in with Craig Shindler, Diane Green (of The Odd Jobs and the Hellcats) and Bob Fordyce (The Odd Jobs, Shagnasty, Grundies, Eldritch Ersatz) in a place just down the road from Fred's Hideout. She later was taken in by Melissa Thornton and lived with her on North Parkway, where Linda entered a new and unprecedented phase of songwriting prolificness. Only she can explain, but I observed, and what I saw was a great release and a quantum leap in confidence. There was also a geeky technical thing which i think affected her writing. Around this time, her then-boyfriend, Philip Tubb, keyboardist with the band Rin Tin Horn (along with Jack Yarber, a.k.a. Oblivian), had given her the blue Fender Mustang she still plays today, and I think John McClure's brother-in-law Don, who was a country session musician and owned a recording studio in North Mississippi (or perhaps it was John himself) had played her a guitar strung with just the high strings from a 12-string guitar. This will probably mean nothing to the non-guitarist, but it sounds different, let's leave it at that. Anyway, Linda strung her Mustang the same way, and to my ears the songs she wrote during that era sound different from everything she had written before or since.

We had all become friends and fans of K9 Arts, consisting of Jim Duckworth on guitar, Craig Shindler on bass and vocals, and Rich Trosper on drums. They were as different as they could be from us in style and approach, but a rapport was struck, and we began playing shows together, with Rich joining us on drums. New drummer, new songs, and a new sound. Rich was an amazing drummer, very intuitive, with a very sensitive grasp of dynamics, who also believed in injecting tension (true to his love of Tony Williams), but never annoying or unduly flamboyant. Refinement seemed to be his defining characteristic. He was good-humored and full of surprises. I knew that he had an undying love of prog-rock drummers, so much so that he told me he chose his little house near Memphis State on the basis of the address alone - 2112. Yet, on the few occasions when I actually visited said house, the only records I found on display were old jazz 78s, hundreds of them.

We never recorded with Rich, apart from one song ("Looking 4") at Doug Easley's backyard studio and some very good live tapes I made at the old Barristers downtown (this was the small place, not the second, larger Barristers, into which I had the pleasure of booking the first gig in 1991). The relationship between the two bands was great, and we always made a point of honoring K9 Arts by playing our version of their signature instrumental, "Tav," as a mark of respect. Linda wrote songs for each band member, two of which appear on "The Lost Album": "Laff" was written for Jim Duckworth, and "Today," which I think is one the best from that era, was written as a wish for Craig to help him through a low point. There was another song called "After Talking," written for Rich, but it was only played live a few times as part of the "K9 Trilogy" and never recorded. There are probably others that I can't remember or don't know about, which were written as messages to individuals.

I went back to Japan in August 1988, for two years. It was a tough decision to take given the apparent momentum the band had, but everyone was very supportive. I think LHTW played a few times after my departure as a three-piece, but subsequently became dormant. Upon my return, we played a few times at the second, larger Barristers, under both the LHTW name as well as "Linda Heck and the Yes Men" (thus the poster image above - the only Linda Heck one I have in my possession) either in an "unplugged" configuration, or with the fabulous drummer Keith Padgett. The story in the 1991 - 1992 period, however, was mostly about the recording of an album still unheard by far too many. The songs written during the Rich Trosper-vintage LHTW period form the core of the 21 songs found (or not found, as it were), on what I continue to refer to as "The Lost Album," recorded with Doug Easley and Davis McCain at Easley-McCain studios in 1991 and 1992. This remarkable recording deserves its own post, which I will write in due course.

I continue to be in frequent contact with Linda, and have the utmost respect and admiration for her song-writing and singing, so it thrills me to note that she is back with a vengeance. Check out 10 songs on her MySpace page, including two new tracks recorded with John McClure, and eight from "The Lost Album." She seems totally reinvigorated, transformed, and I'm supporting in any way I can from my Henchperch here in a rainy South London. It makes me smile to note that the third member of her current trio, drummer Kurt Ruleman, was the first drummer either of us ever played with in a real band. So, 23 years and umpteen drummers later, she's back at the source, in a sense. I couldn't be happier for her, and can't wait to see where the new road takes her.

Labels:

James Enck,

John McClure,

Linda Heck,

Rich Trosper,

Roy Brewer

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)